It seems that in the past few years Truman Capote has transcended his status as a writer. The subject of two biopics (Capote and Infamous, released in 2005 and 2006, respectively), Capote also threw the famous Black and White Ball that was the topic of a recent book (Deborah Davis’ Party of the Century: The Fabulous Story of Truman Capote and His Black and White Ball). This recent Capote-mania has sealed his status as cultural icon, a position that isn’t dependent on his literary output, which gets a re-examination in Portraits and Observations: The Essays of Truman Capote.

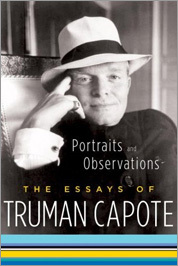

It seems that in the past few years Truman Capote has transcended his status as a writer. The subject of two biopics (Capote and Infamous, released in 2005 and 2006, respectively), Capote also threw the famous Black and White Ball that was the topic of a recent book (Deborah Davis’ Party of the Century: The Fabulous Story of Truman Capote and His Black and White Ball). This recent Capote-mania has sealed his status as cultural icon, a position that isn’t dependent on his literary output, which gets a re-examination in Portraits and Observations: The Essays of Truman Capote.Released in late 2007, the book is a collection of all the essays Capote ever published, some of which haven’t been released since their initial publication. The book seems to be an attempt to revive Capote’s reputation as a serious writer, and though hardly successful overall, some of the essays are a delight to read.

The chronological arrangement of Portraits and Observations traces the arc of Capote’s writing career. His body of work undergoes a distinct change around the time of In Cold Blood’s publication in 1966 — early pieces that are bright and promising give way to weary essays that miss their mark. Capote’s writing, like his life, peaked with In Cold Blood, a novel that drove him to drink and resulted in a steady decline in literary success.

The essay topics in Portraits and Observations are wide-ranging — everything from travel snapshots to meditations on celebrities to Capote himself comes under his discerning eye. His writing is descriptive and rich, and his slightly longer observations are the best examples of his nonfiction writing, suggesting that it generally takes more works for Capote to successfully present his subjects — despite believing himself to be a “spare” writer.

A snippet of “Self-Portrait” explains Capote’s seeming arrogance in his work:

Honestly, I don’t give a damn what anybody says about me, either privately or in print. Of course, that was not true when I was young and first began to publish. And it is not true now on one count — a betrayal of affection can still traumatically disturb me. Otherwise, defeat and criticism are matters of indifference, remote as the mountains of the moon.A number of the 42 pieces are fine examples of what Capote can do, but there are also some that are simply frivolous — self-interviews with Capote give us insight into his psyche, but don’t do much to help his literary reputation. The same is true with brief snippets culled from a book he did with Richard Avedon — these “portraits” don’t really say anything about their subjects (on director John Huston — “He is a man of obsessions rather than passions, and a romantic cynic who believes that all endeavor, virtuous or evil or simply plodding, receives the same honorarium: a check in the amount of zero.”)

A later highlight is “Handmade Coffins,” Capote’s “nonfiction account of an American crime” from 1979, written as an interview and achieving the narrative voice that Capote seems to lose sight of as time passes. Other compelling pieces are “Lola,” a story about Capote’s pet raven, and the famous 1956 profile of Marlon Brando, whom Capote meets at a hotel in Kyoto.

Portraits and Observations begins with a look at New Orleans, where he was born, and leads into essays about a New York and Brooklyn that seem to be indistinguishable from the Southern city. The book closes with “Remembering Willa Cather,” which Capote wrote the day before his death in 1984, and touches on his relatives in New Orleans and Alabama. Each of his writings is imbued with an inescapable nostalgia for the South — despite calling the Big Apple his city, his writings suggest that the tormented writer never really left his bittersweet childhood behind.

This review was originally published in the Washington Blade.

No comments:

Post a Comment